Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.

While Kengo Kuma and Associates has been producing work for 26 years, the event with which the narrative of the practice hinges upon took place in 2011, after the devastating tsunami off the Pacific coast of Tōhoku destroyed thousands of lives and homes and left many towns in ruin. For Kuma, the tsunami was an almost paradigm-shifting event, forcing him to confront prevailing contemporary attitudes toward the built environment and its relationship with nature.

Sunny Hills Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

Citing a Japanese proverb that insists “weakness is strong,” Kuma concludes that the Japanese of the preindustrial era possessed “a wisdom of how to live with the tsunami,” which was forgotten in the 20th century by the design community’s mounting faith in the resiliency of industrial materials, such as concrete and steel. In examining pre-20th-century society’s dependence on local materials, much of Kuma’s work of the past decade has demonstrated thorough explorations of the application of natural materials, particularly timber, and also of traditional craft techniques, such as chidori wood joinery and thatching.

Kuma, who strives to achieve a “humbleness” in architecture by dissolving or de-solidifying the structural elements of his projects, demonstrates his ability to dramatically shift the scale of his work without compromising the delicacy and lightness that defines his work. Architizer chatted with Kuma about the evolution of his architectural thinking, and of his firm’s work, over the past few years.

Starbucks Coffee at Dazaifutenmangu Omotesando, Dazaifu, Japan

Read on for our discussion on preindustrial values, the significance of material research and the detachment of contemporary architecture:

Joanna Kloppenburg: You’ve mentioned before that in the 20th century people lost their respect for nature, and this was reflected in the architecture of the time. Can you speak a little bit more to how values of preindustrialized society became an integral examination of your practice and how the 2011 tsunami influenced that way of thinking?

Kengo Kuma: I think in the preindustrialized era, the community has a local circulation of material; they are using local goods and that kind of measure of circulation is the basis of their life. After the industrialized era, people forgot that kind of natural circulation and that respect with nature.

And then the community was totally destroyed. The tsunami was very shocking for us because the tsunami reveals that kind of thing. Communities in the preindustrial era had a wisdom of how to live with the tsunami, but we forgot that kind of wisdom totally. After the tsunami, I began to think about how to bring back that kind of wisdom to the society. There are a lot of architects for whom this is very important because, through architecture, we can show that kind of circulation by using local material and working with local craftsmen, and that is the basic idea of my practice.

Yusuhara Marche, Takaoka District, Japan

Is that a particularly important aspect for you, to seek out local community members or craftsmen that can participate in the design of your projects?

Yes, I want to push for the participation of the local people in any of my projects. In our public projects, we often hold workshops with the local people about the actual design and their participation brings the building a kind of energy. After the completion of the building, each person who participated in the process of design is very happy to use the building, and then we can get more visitors to the building.

A good example is Nagoaka City Hall: We did many workshops with the local people, and we involved children and elderly people with the development of the project. After the completion, we had many many visitors to the project. In one year, 1.2 million people visited that city hall, which is very surprising for that kind of public building.

Nagaoka City Hall, Nagaoka, Japan

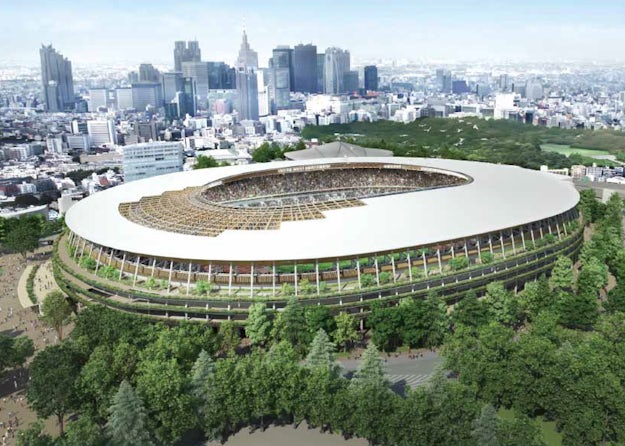

You’ve mentioned that you would like your work to challenge the 20th-century notion of the value in volume. How do you maintain this approach in a large-scale project, such as the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Stadium, that requires such tremendous engineering work?

The collaboration with the engineer is always very important, and the approach to the project is to involve the engineer from the beginning of the project. The beginning of the project is a very important period, and in that first stage I try to draw out the idea for the engineers as much as possible.

For example, for the National Stadium, I asked the engineers how to decrease the size of the structure as much as possible, and then when they understood my idea and my philosophy, finally were we able to decrease the height of the building from 75 meters [250 feet] from Zaha Hadid’s first scheme to 49 meters [160 feet] for my scheme. We drastically decreased the volume of the building through a smooth communication with the engineers. Some architects start with their own idea for the shape of the building and the structure is applied afterwards, but I think this is not healthy. I think we should start with the discussion of structure.

2020 Tokyo Olympic Stadium; via Dezeen

How does your sensitivity to materials factor into this process?

I think the material should not be used for the surface of the building. Materials can show the philosophy of the project and so we carefully choose the main material of the building from the first stage of the project. The good thing about starting with materials in the process is that we have enough time to do the research about the materials, because if we try to use a new material, we need a lot of time.

From the beginning of projects, we start the research with the materials, and then we can find the essence of that material. The use of material in our projects is not for the surface of the building, but is often used for the main structures, and most of the structure is supported by the same material. By that approach, that kind of integration became possible.

Yusuhara Wooden Bridge Museum, Takaoka, Japan

Much of your work employs very traditional Japanese techniques of wood joinery. Had these techniques always been an essential part of your practice?

The education system in Japan is still mainly teaching the uses of concrete and steel, and when I was studying in Tokyo University — which was 30 years ago — the education system was much more concrete oriented. However, one unique teacher taught me the traditional joinery system in Japan, and I was so impressed by his lecture and by the real samples of those joineries. It was so beautiful, and my experience with this encounter made me want to go in that direction.

Now I am teaching in the university, and I try to bring more specialists about that tradition. We have a Ginza workshop with the craftsmen, and I hope it can change the students’ mentality and the students’ attitude to building.

GC Prostho Museum Research Center, Kasugai, Japan

The Darling Exchange building in Sydney sees a new application of wood for your practice: The wood is not joined or stacked, rather it’s bent and wrapped. What led you to experiment with this technique?

For Darling Harbour, the location is very unique; it also has interesting neighbors, as both Chinatown and the water are very close. I want to create the unique monument in that kind of special location. The idea is to create a spiral which draws people to that new community center, and also that spiral is meant to bring people up to the top of the building, that idea is similar to the Guggenheim idea of Frank Lloyd Wright.

The Darling Exchange, Sydney, Australia; via Business Insider

Why is it important to you that architecture as structure not be imposing?

I always think that architecture should not be the protagonist of the environment. Architecture should work with the environment and should not be separated from the environment. The most important part of architectural design is the interface between the environment and architecture, and for that reason I try to minimize the existence of architecture, to minimize the volume as much as possible, and through that process, people can feel comfortable with the communication of the building.

That kind of comfort is a goal of architectural design. Today, a unique shape should not be the goal of the design. We always use the word humbleness in the design process. If the architecture looks elegant but not humble, people will hate architecture, and that is the worst situation for architectural design.

Oribe, Miami, Fla.

Do you find a lot of contemporary architecture to be alienating?

Yes; the goal of the contemporary building for the investors is just to catch the people’s attention. They just want to sell the building, and that kind of attitude often creates a very arrogant building because it stands out from the context of the site. After they have sold the project, it is a big a waste left to the city; [which can be] very bad for the city.

Top: China Academy of Art’s Folk Art Museum, Hangzhou, China; bottom: Wuxi Vanke, Wuxi, China

In your international projects, how do you maintain the Japanese values embedded in your approach while being sensitive to a project’s particular environment?

I don’t want to push my ego into every project; I want to hear the opinion from the community each time. For example, for the Darling Harbour project we had many discussions with the community, and in China we also had a discussion with the local people, professors and designers. Through that process, I try to understand the tradition of the place as much as possible and also try to understand its current situation.

China Academy of Art’s Folk Art Museum, Hangzhou, China

Because of those discussions, our design for those projects is very different each time. Some architects criticize my work, saying there is no consistency between my projects. On the contrary, I think that we have a strong consistency in our approach: Taking that attitude means that architects ignore the place, and I don’t want to do that. For each project, I can learn many things from the place, and it’s always a very exciting experience for us.

Interview edited for clarity. This interview was originally conducted in 2016 and has been adapted for republication in 2020.

Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.

The post The Humble Revolution: Kengo Kuma’s Fight Against “Arrogant, Alienating” Architecture appeared first on Journal.